Hildegard of Bingen:

A Music of Light

by Margaret Donsbach

The earliest composer whose name and music we still know was a medieval nun who lived in the obscurity of an anchorite's cell until she was middle-aged. Though never trained in composition or musical notation, she wrote over 150 songs, mysteriously beautiful and fiercely difficult to sing, that have been preserved to this day. She believed her music was inspired by God.

Hildegard of Bingen was forty-two when a vision and a "voice from Heaven" transformed her life. "Heaven was opened," she said, "and a fiery light of exceeding brilliance came and permeated my whole brain, and inflamed my whole heart and my whole breast."

The voice demanded that she "speak and write" about her visions, but she hesitated. Medieval church authorities took heresy seriously, and religious images and ideas permeated Hildegard's visions. But when she finally did share her visions, she grew bold enough to chastise popes.

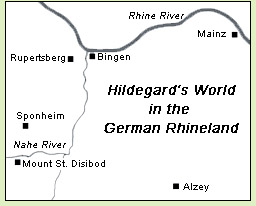

Born into a large family of German nobility in the Rhineland near Alzey in 1098, Hildegard was always different. "In my third year of age," she wrote, "I saw so great a light that my soul trembled, but, because I was still an infant, I could not convey anything about it." According to one story, she predicted the birth of a white calf marked with variously colored spots on its forehead, back and feet, which in due course was born with the markings she described.

When she was eight, her parents dedicated her to a religious life. She became the student and companion of Jutta, a girl of fourteen who had vowed herself to God and virginity. The beautiful, nobly born Jutta refused to marry, instead cultivating piety under the supervision of a devout widow, perhaps at Jutta's own home in Sponheim or as a lay-sister attached to a nearby monastery. From Jutta, Hildegard learned to read and write Latin, though she would always lament her imperfect grammar. It was probably from Jutta that she learned the basics of herbal medicine. She also learned to sing the psalms of David and accompany herself on the ten-stringed psaltery, a plucked instrument resembling the zither.

When Hildegard was fourteen, she and another girl joined Jutta and "died to the world." A funeral ceremony with lit tapers and songs for the dead solemnized their transformation into anchorites at the Benedictine monastery of Mount St. Disibod a few miles south of Sponheim. The monks built a new stone wall sealing the women into a side area of the monastery, leaving only a small window through which provisions could be passed and visitors could speak to them.

Under Jutta's authority, the girls ate frugally and wore rough clothing. Their pleasures were few, although Jutta did not require them to follow her own extreme regimen of fasting, keeping vigils that deprived her of sleep, and spending hours of prayer standing barefoot on the cold floor. Hildegard already suffered from a mysterious illness - probably a form of migraine - which gave her frequent attacks of crippling pain. Ecstatic, light-filled visions accompanied them.

Hildegard wrote that at age 24, "I saw an extremely strong, sparkling, fiery light coming from the open heavens. . . . And suddenly I had an insight into the meaning and interpretation of the psalter, the Gospel and the other Catholic writings of the Old and New Testaments. . . ." In the cramped anchorites' cell, she said as little as possible about her visions. A year earlier, the influential Cistercian abbot Bernard of Clairvaux had prosecuted and imprisoned Peter Abelard for writing a book expressing unorthodox ideas about the Trinity.

Over the years, Jutta's reputation for sanctity attracted more families to offer their daughters to her and God. The "tomb" would be opened so another girl could be pronounced dead to the world and sealed inside. Eventually, the little convent included a dozen nuns. Through their cell window, they could hear the monks singing the divine office at regular hours of the day and night. Perhaps the music was a solace to Hildegard, deprived of most sensory pleasures except those that came with her visions.

Jutta's extreme asceticism affected her health and probably led to her death at age 45. When Hildegard helped prepare her body for burial, she discovered a chain wrapped around it which had carved three furrows into the flesh. With Jutta gone, Abbot Cuno apppointed Hildegard to lead the women's community. She began writing songs for her nuns to sing as part of the divine office.

Her bouts of illness intensified, accompanied by visions which a voice instructed her to share with others. She feared to obey. But then, when she was 42, came the insistent vision that changed her life. "I saw a great splendour in which resounded a voice from Heaven saying to me, 'O fragile human, ashes of ashes, and filth of filth! Say and write what you speak and hear.'"

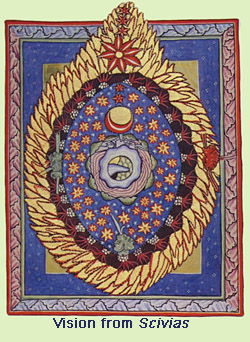

Interpreting her attacks of debility as punishment for her failure to obey the voices, she finally described her experience to Volmar, one of the St. Disibod monks. With his help, she began writing a book she titled Scivias, an illustrated account of her visions with interpretations of their symbolic meaning. Volmar edited and transcribed it, improving the grammar of Hildegard's Latin.

Volmar spoke of their work to Abbot Cuno. Cuno discussed it with his superior, the Archbishop of Mainz. The Archbishop reported it, in turn, to the pope. Soon a delegation of papal envoys arrived at Mount St. Disibod to investigate Hildegard's writing. Agreeing to lend them her unfinished manuscript so they could share it with the pope, she must have realized her fate hung in the balance.

She wrote to Bernard of Clairvaux, who had recently presided over Abelard's second heresy trial and ordered his books burnt. "O venerable father Bernard," Hildegard wrote, "I lay my claim before you, for, highly honored by God, you bring fear to the immoral foolishness of this world." She had been "greatly disturbed by a vision," she said, describing how it had touched her "heart and soul like a burning flame, teaching me profundities of meaning."

She begged for his opinion. In a vision two years before, she had seen him "like a man looking straight into the sun, bold and unafraid. And I wept, because I myself am so timid and fearful." She asked his advice on whether to "speak openly or keep my silence." She was, she told him, "caught in the winepress."

Bernard answered briefly, regretting the "press of business" that kept him from writing at more length. Nevertheless, one sentence must have transfixed Hildegard's attention: "[W]e most earnestly urge and beseech you to recognize this gift as grace and to respond eagerly to it with all humility and devotion."

That winter, during the Synod of Trier, Pope Eugenius read passages of the Scivias to an audience of prominent churchmen. Bernard was present and spoke approvingly. The pope gave Hildegard's work his blessing and sent her an encouraging letter. She answered him in a tone strikingly different from that of her letter to Bernard. She wrote, she said, at God's instruction and hoped to "arouse your spirit to your duty concerning my writings, so that your soul may be crowned."

It was the first in a stream of correspondence with the most powerful and important people of her time. She felt emboldened to address harsh criticism even to popes, because she considered herself only a humble messenger, reporting on visions God had entrusted to her.

Disappointed by one of Eugenius' successor popes, she wrote, "[Y]ou despise God when you embrace evil. For in failing to speak out against the evil of those in your company, you are certainly not rejecting evil. Rather, you are kissing it." To Emperor Barbarossa, she wrote, "Woe, O woe to the evil of those wicked ones who spurn Me. Hear this, O king, if you wish to live." More sympathetically, she wrote to Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, "Your mind is like a wall battered by a storm. . . . Stay calm, and stand firm, relying on God and your fellow creatures, and God will aid you in all your tribulations."

In her writing, Hildegard championed orthodox religious doctrines, but her convictions led her to behave with unorthodox boldness. She wrote that women were inferior to men and should not preach, yet she embarked upon church-approved preaching tours. When Odo of Soissons, who taught at the University of Paris, asked her to explain the Trinity - the concept that had undone the learned Abelard - she complied, bolstered by her visions. "God is plenitude," she told him, "and that which is in God is God. For God cannot be shaken out nor strained through a sieve by human argument, because there is nothing in God that is not God."

A priest asked her for advice on "the proper and improper ways" to celebrate the mass. This was an exclusively male function, but she did not hesitate to answer. She told him that a believer receiving the sacrament from an unworthy priest would nevertheless be "illumined as by the brilliance of the sun" - a conventional answer, expressed in Hildegard's own vivid style.

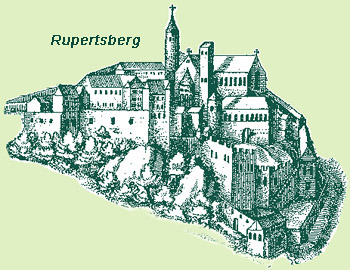

Young noblewomen continued to join her community, as they had done in Jutta's day. By 1150, Hildegard was caring for eighteen nuns in the enclosure originally intended for three. God, she told the abbot, had revealed his will to her in another vision, instructing her to establish a separate monastery of her own and showing her a hill by the Rhine River where St. Rupert had lived and was now buried. Faced with a divine command, Abbot Cuno did not refuse. Instead, he and his monks dragged their feet. Hildegard's fame had inspired a considerable stream of revenue to flow into the St. Disibod coffers.

Delayed and thwarted, Hildegard fell ill. A pair of minor miracles were later said to have followed. Her most vocal opponent's tongue suddenly swelled so big he could not close his mouth over it. When he vowed to oppose her no longer, he recovered at once. The abbot visited her cell and found her "utterly paralyzed, like a pile of heavy stones." He could not budge her, even with the aid of a lever. Persuaded her illness was "a divine chastisement," he authorized the move. With that, "she rose up very sprightly," amazing everyone present.

Hildegard bought St. Rupert's Mount, paying for it with donations and an exchange of property from Mount St. Disibod's holdings. She negotiated her new establishment's financial independence, although monks from St. Disibod would continue to provide the women with services such as a priest to say mass and a secretary - Hildegard's faithful friend Volmar - to assist with her writing. She was abbess of the new St. Rupert's Mount monastery in all but name.

In contrast to Jutta, Hildegard opposed severe asceticism. When people fasted excessively, she believed, "weariness sets in, and, as a result, vices flourish more than if the body had been nourished properly."

A disapproving correspondent described her nuns' clothing. "They say that on feast days your virgins stand in the church with unbound hair when singing the psalms and that as part of their dress they wear white, silk veils, so long that they touch the floor. Moreover, it is said that they wear crowns of gold filigree, into which are inserted crosses on both sides and the back, with a figure of the Lamb on the front, and that they adorn their fingers with golden rings."

The design of the coronets may have been inspired by a vision Hildegard described in Scivias: "I saw . . . a great crowd of people, brighter than the sun, all wonderfully adorned with gold and gems. Some of these had their heads veiled in white, adorned with a gold circlet; and above them, as if sculpted on the veils, was the likeness of the glorious and ineffable Trinity . . . and on their foreheads the Lamb of God . . ."

Vigorously, she defended her nuns' attire. Conceding that a married woman "ought to preserve great modesty," she nevertheless held that a virgin dedicated to God should enjoy a different rule, "for she stands in the unsullied purity of paradise, lovely and unwithering." In Hildegard's community, each nun wore white as "the lucent symbol of her betrothal to Christ."

Central to Hildegard's philosophy was the concept of viriditas, a Latin word meaning "greenness." Hildegard used it to express the mystical essence of the life force, both earthly and spiritual. She believed the deep green color of emeralds endowed them with healing properties. According to her metaphor, emeralds draw in viriditas as a lamb sucks up milk. On the spiritual plane, viriditas helped lift the soul to God. "The intellect in the soul is like the greenery of the tree's branches and leaves, the will like its flowers, the mind like its bursting firstfruits, the reason like perfected mature fruit, and the senses like its size and shape."

Unlike theologians who taught that the body had to be subdued and broken before the soul could flourish, Hildegard believed body and soul supported each other. She taught that "the soul emanates the senses. How? It vivifies a person's face and glorifies him with sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch, so that by this touch he becomes watchful in all things. For the senses are the sign of all the powers of the soul, as the body is the vessel of the soul." Song, she believed, was a powerful symbol of this union: "the words symbolize the body, and the jubilant music indicates the spirit."

People of Hildegard's time believed the earth lay at the center of a set of revolving heavenly spheres which gave forth musical harmonies, even though people on earth could not hear them. The idea originated with the ancient pagan Greek philosopher Pythagoras. Aristotle described how the Pythagoreans conceived of the cosmos: "[W]hen the sun and the moon, they say, and all the stars, so great in number and in size, are moving with so rapid a motion, how should they not produce a sound immensely great?" Because measurements of the planets' speeds and distances seemed consistent with the mathematical ratios between musical notes, they concluded, said Aristotle, "that the sound given forth by the circular movement of the stars is a harmony."

Hildegard wrote that before Adam's fall, he was able to hear and sing with the angels. "For, before he sinned, his voice had the sweetness of all musical harmony. Indeed, if he had remained in his original state, the weakness of mortal man would not have been able to endure the power and resonance of his voice."

As abbess, Hildegard was responsible for leading her community in chanting the divine offices eight times each day. These began before daybreak with matins, then continued with lauds, prime, terce, sext, none, vespers and, before retiring for the night, compline. The style of the music she wrote for her nuns to sing is distinctive, filled with melismas, long melodic passages sung on a single syllable. Other religious composers used melismas to express joy in Easter and Christmas music, but Hildegard used them liberally in music for all seasons and purposes.

Near the end of her life, church authorities punished St. Rupert's Monastery for burying a man in its cemetery whom they believed - incorrectly - to have died while excommunicated. They banned Hildegard and her community from singing the divine office.

She obeyed, but wrote her superiors a furious letter, saying "a vision, which was implanted in my soul by God the Great Artisan before I was born" compelled her to protest. She warned that "those who without just cause, impose silence on a church and prohibit the singing of God's praises . . . will lose their place among the chorus of angels, unless they have amended their lives through true penitence and humble restitution."

Six months before Hildegard died, the Archbishop of Mainz rescinded the ban. Hildegard and her nuns were able to raise their voices in song once again. She had lived over eighty years, plagued all the while by her mysterious illness but supported by the visions and voices that came with it. Conscious of her inferior education, she had nevertheless dared to instruct popes and emperors, to fight for authority over her own monastery, and to manage it according to the inspiration of her visions. She saw herself "like a trumpet, which only returns a sound but does not function unassisted, for it is Another who breathes into it that it might give forth a sound."

Fifty years after her death, the church began investigating whether to declare her a saint. One witness, an elderly lay sister, described how when Hildegard was "irradiated by the Holy Spirit . . . she would walk about the monastery singing that sequence inspired by the Holy Spirit which begins 'O virga ac diadema!'"- "O branch and diadem." It was a song of praise to the Virgin Mary, who erased the sin of Eve.

It unfolds in sinuous melodies reminiscent of Arabic-influenced troubadour music. Abruptly, airily, the melody rises, and then plunges to mysterious depths, rippling and swaying like the coruscating lights of Hildegard's visions. Metaphors from nature pervade the lyrics. "Tu frondens floruisti," she sings, "Burgeoning, you blossomed." Her praise of Mary seems to embrace all the sisterhood of women: "O great is the strength of man's side,/From which God took the form of woman,/And made her the mirror of all adornments/The clasp of his entire creation."

Recordings of Hildegard's Music:

click on the title to link to an online source

A Feather on the Breath of God

Hildegard von Bingen: Heavenly Revelations

Hildegard von Bingen: Symphoniae

Further Reading:

click on the title to link to an online source

Hildegard of Bingen: A Saint for Our Times by Matthew Fox (2012).

Vision: The Life and Music of Hildegard von Bingen by Jane Bobko

Hildegard of Bingen: A Visionary Life

Scivias, by Hildegard of Bingen, translated by Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop

The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen, Vols. I, II and III, translated by Joseph L. Baird and Radd K. Ehrman

Hildegard of Bingen: The Woman of Her Age by Fiona Maddocks

Voice of the Living Light: Hildegard of Bingen and Her World by Barbara Newman

Jutta and Hildegard: The Biographical Sources

Fiction:

Illuminations by Mary Sharratt (2012)

Back to Medieval European Continent: 12th and 13th Century